Oberst Herbert Selle, German Army, Retired

Translated and adapted by Mr. Karl T. Marx

Taken from the Military Review - Volume XXXVII - October 1957 - number 7

Archive Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Ever since General ( Friedrich) Paulus had flown into the kessel on 21 November 1942 (only two days after the Russians had closed their pinchers) he had formulated plans to break out and unite his troops with those fighting on the Don-Chir front. This course did not appear impossible.

German troops had accomplished it before with great success and the spirit around Stalingrad was such that every man would have done his utmost to get out and make contact with outside forces.

General Paulus held a meeting with all his corps commander and it was quickly agreed to contact Hitler to obtain permission to: .

HAVE THE SIXTH ARMY BREAK THROUGH AT THE SOUTHWEST SECTOR, OF THE KESSEL, BY CONCENTRATING ENOUGH TANKS AND TROOPS TO MAKE THIS POSSIBLE, AND THEN OPEN A PANZER (TANK) BORDERED ALLEY THROUGH WHICH ALL TROOPS AND NEEDED EQUIPMENT CAN BE FUNNELED OUT TO MAKE CONTACT WITH GERMAN TROOPS IN THE DON-CHIR AREA.

Everyone agreed and all were confident that this fairly simple measure would be approved. About 100 heavy tanks, ready for action, already were in line. Troops began marching to their jumping off places, showing a new measure of confidence and hope. Another keesel would be broken, perhaps another glorious Kharkov.

But on 23 November a telegraph message from Hitler-ordered the Sixth Army to stay inside the encirclement and to wait for relief from the outside.

Von Seydlitz Enters Plea.

This order hit the generals and those acquainted with their plains like a stroke of lightning. Hope and daring were paralyzed and many a man faced a real, hard test of obedience versus commonsense and the strong drive forself-preservation. General von Seydlitz wanted to ignore the order and initiate the breakout. On 25 November he handed General Paulus a memorandum in which he prophesied in a shocking way the debacle of the Sixth Army in event it obeyed the orders of Hitler and did not break out toward the west or southwest during the next few days. Some sentences of this touching, impressive memorandum may be quoted:* ( Published here for the first time.)

"To undervalue the spirit of the enemy in a situation so favorable to him and not to believe him capable of the only right action has always involved defeat in war history. It would, therefore, be an unequaled va-banque plug that would cause not only the catastrophe of the Sixth Army but also have the gravest consequences for the final result of the entire war. The order of Hitler to keep the igel (encirclement) and to wait for relief from outside is founded on an absolutely unreal basis.

It cannot be carried through and its consequences must be the debacle. It is, however, our holy duty to preserve and save our divisions, therefore, another order must be given or another decision be taken by the army herself. Our army has only the alternative of the breakthrough toward the southwest or ruin within a few weeks, We are morally responsible for the life or death of our soldiere. Our conscience toward the Sixth Army and our countty commande ue to refuse the orders of Hitler and assume for ourselves freedom of action. The lives of some hundred thousand German soldiers are at stake. There is no other way."

General Paulus and his chief of staff–in spite of all doubts and scruples—could not agree to General von Seydlitz’ passionate views. After a long inner struggle they made up their minds to comply with Hitler’s orders. As a consequence, all previously ordered movements of tanks and troops were halted, and orders went out to start the einigelung, the process of rolling up like a hedgehog and waiting for the enemy to attack.

Orders Without Support.

Hitler’s orders. were typical of the man, typical of his wishful, unrealistic thinking.

Einigelung-hedgehogging-meant dugouts, trenches, heavy digging equipment, winter uniforms, special underwear, heavy gloves, and special oil for trucks. It meant a soft soil for digging, not 30 inches of snow; not soil as hard as rock. It meant plenty of winter clothing, supplies, tools —and of all these things the Sixth Army had virtually none. Swarms of Russian fighter planes followed the few German relief planes almost down to the snow covered airfields. Ammunition dwindled; so did supplies. Rations had to be cut againand again. And there were only two makeshift airfields left. “Hitler’s decision, it was learned later, was made after Reichmarshall Goring had assured him that his air force would be ready and able to supply Stalingrad with all needed supplies. Goring’s chief of staff, General Jeschonnek, had counseled against such impossible, nay, criminal promises, but was overruled. (General Jeschonnek committed suicide after the tragic Stalingrad ending.)

We in Stalingrad computed hard and harsh figures, factual figures, about such a boasted airlift. We would need 1,000 landings a day to obtain 750 tons of needed goods. Tyfly 1,000 planes a day would require another 1,000 planee for replacements due to attrition. We needed tools and gasoline, hundreds of mechanics, repair shops—and we had only two small airfields left. (After 14 January 1943 there were only one.)

Hollow Air Promises.

The tragedy of Stalingrad largely is a tragedy of the German Air Force, since Hitler’s decision was based-on Goring’s boast that he would supply the beleagured troops. Instead of 1,000 planes a day there were 50 to 70 at first, and then never more than 26 planes a day, often only 15. The greatest amount of provisions, ammunition, and gasoline flown in during one day was 105.5 tons. After the pitomnik airfield was lost on 14 January very few pilots dared o; were able to land at the remaining field at Gumrak. All they could do, after having escaped swarms of Russian fighters, was to drop their supply packets and then turn tail. Slowly, hunger started its job of strangulation. And far away, in a gaudy uniform, Herr Reichmarshall Goring dined and wined and boasted about his invincible air armada—until even Hitler realized that his boon companion had put one over on him, that the promise of a Stalingrad airlift was a cruel hoax, and that 300,000 men were doomed unless something was done and done quickly. It mattered little now that Reichmarshall Goring was no longer consulted, nor even permitted to share the august presence of his one-time companion. The Sixth Army was starving, dying, freezing to death, almost waiting for the coup de graice. Napoleon must have been grinning in his tomb in far away Paris. He knew the Russian steppes—he knew the long, trackless wastelands, the snow, and bitter cold of Russia.

Relief Attempt Fails.

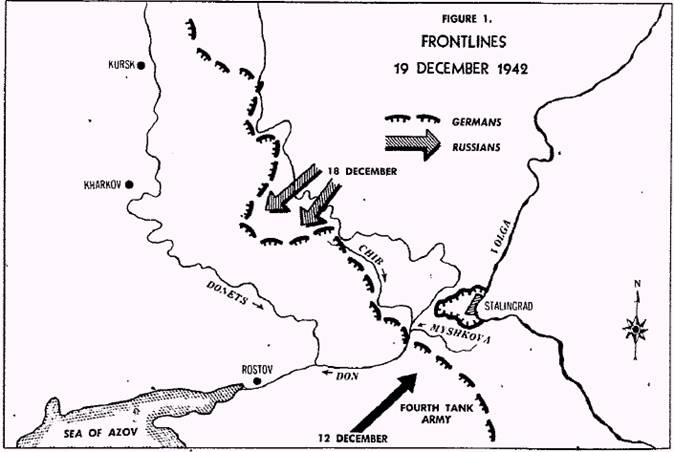

At the beginning of December 1942 there was new hope. On 12 December Colonel General Hoth with his Fourth Tank Army started from Rostov up the Don River to relieve Stalingrad. (Figure 1.) We staff officers knew, however, that this Fourth Tank Army contained only one strong tank division and two seriously mauled tank divisions. In spite of this they succeeded at first in their northward thrust and gained 55 miles. Again General Paulus asked permission to break out to make contact with General Hoth. With this he was in full accord with Colonel General von Manstein, chief commander of the army group Don. Manstein had done everything possible to accomplish the breakthrough of the Sixth Army in those days. But again permssion was denied, and this time there was almost open rebellion at Sixth Army Headquarters. However, General Paulus obeyed once more. It must have been a hard struggle for this gentleman-soldier to obey the order.

So Near, Yet So Far.

The Fourth Tank Army now was only 30 miles from the Stalingrad southwestern perimeter. Had General Paulus attacked, had he ignored the commands of Hitler, had he linked up with Hoth and then hastened to Hitler to offer his head for breaking out and saving 300,000 men, the end might have been different. But he did not. On 23 December Colonel General

von Manstein was forced to withdraw the elite of Hoth’s “tank army,” the 6th Panzer Division, from the front of theeounterattack in order to master a formidable situation arising from a Russian break-through at the front of the Italian army corps (Figures 1 and 2). This Italian collapse threatened the entire area as far as the Black Sea. Colonel General Hoth had no other alternative but to fall back, leaving Stalingrad to its fate.

Now another hasty and costly retreat. To make matters worse, on New Year’s Day Hitler sent to the Sixth Army his special and personal greetings plus his renewed assurances that everything was being done to relieve Stalingrad!

Only among friends did we voice our thoughts and beliefs. We no longer had any trust in anything Hitler said or did, His orders to us appeared to be those of a man obsessed with an insatiable drive for power and a complete lack of understanding of the realities of war. He lacked a sense of value, of mass und Ziel.

Life Within the kessel.

To keep an encircled army of roughly 300,000 men alive is a task that no supply genius, cut off from replenishing sources, has ever solved. Provisions at Stalingrad never had been plentiful, and it now became a matter of cutting rations to the very minimum. Here, again, there was no way to figure out how to stretch, how to cut, how to keep going, at rock bottom rations, until Hitler’s often promised push toward us would relieve all pressure and bring food and supplies aplenty.

The matter resolved itself into a question of whether to eat more and give up sooner or eat less and keep going until the last can of food had been emptied.

It was decided to eat less and that is truly an understatement. Beginning in january 1943 each of us received a daily ration of about three bunces (75 grams to be exact) and a daily vegetable ration of two pounds for 15 men. Potatoes and meat were unavailable, except the “meat” we hacked out with axes from the frozen horse cadavers lying all around us. The horses of the encircled infantry divisions hadlong been slaughtered for their meat.

Water was nowhere available on the Russian steppes —we had to obtain it by melting snow. Slowly the once proud Sixth Army became an army of walking skeletons with no relief in sight.

Surrender Is Demanded.

During the first week in January 1943 Russian officers; under a flag of truce, approached our northern front to ask for surrender. Some of us felt that the conditions contained honorable terms, even permitting our officers to keep their side arms.

We did not know then that one could’not have confidence in their promises.

On the other hand, the offer ended with threats of complete annihilation of the Sixth Army within a very short time.

Although the offer was discussed among various staff components, General Paulus had little choice but to decline—Hitler all too frequently had yelled about the "no surrender” determination of “his’” armies. Of course, the “Fuhrer” declined as he had also declined a previous request by General Paulus to grant the Sixth Army freedom of action. Again General von Seydlitz counseled to strike—even against Hitler’s orders.

Plan Final Defense.

On 9 January the chief of staff requested my presence. He believed the Russian attack would start toward the end of January and that it would be directed against the Marinovka salient in the Karpovka valley in an attempt to wrest from us the rather favorable terrain with its natural defenses and prepared dugouts.

From that point on they would then try to drive us onto the steppes where there would be no fortifications, no hills, no river banks—only snow and ice and flat country. I was ordered to reconnoiter and work out with the sector commanders an approximate line running southward from the east bank of the Rossoshka River near Nizhne-Alekseyevskiy toward Rogachik on the Karpovka River in case the Russian attack succeeded in crushing the German Marinovka salient.

Contemplating the construction of fortifications in snow, ice, and howling winds with nothing more than light equipment in the hands of troops half alive, I went on my way with heavy heart. It was too late.

The next day, 10 January, the Russian attack began—fully 15 to 20 days earlier than the Gerrnand High Command had anticipated.

The command, however, was right as far as the point of attack was concerned. It hit the German 76th Division north of the Karpovka River, first a concentrated, heavy artillery bombardment and then the tanks, In a short time Russian advance elements had reached the 76th command post and there was no longer any point to explain my mission about a newline of defense. We had to retreat.

Slowly hysteria mounted in the wild battle melee that ensued. More and more the kessel was contracted, with German troops stumbling over the steppes toward the center, away from the tank-haunted, fiery, and murderous perimeters. Stalingrad itself was now the only hope. Its ruined houses, factories, and giant apartments meant shelter and a measure of relief from the howling, tearing winds of the steppes, and the deadly, chilling cold.

Hundreds of wounded men stood along the hardly visible roads, pitifully looking at our car. Some held their crutches aloft in a final, pleading gesture. Some-just stared resignedly. I stopped the car and succeeded in placing 12 wounded men inside, on the roof, on the running board, and mud guards, while I sat on the motor hood, precariously balancing myself as the driver bumped along the icy road. We stopped at the field hospital in Gumrak and there I left the grateful men in the care, of our medics.

Retreat Into Nothingness.

On 14 January the airfield at Pitomnik was precipitously evacuated, largely due to gripping panic among rear echelon personnel who imagined Russian tanks where there were none. Fear struck everywhere, generating an understandable urge for self-preservation that blotted out any sense of discipline or order. General Paulus and the chief of staff were furious at this unsoldierly behavior and at the unwarranted evacuation in the face of an enemy who was, in fact, still one mile away.

Somehow the panicked troops rallied at the hard, decisive word from above and promptly reoccupied the needlessly abanddned Pitomnik airfield. The Russians, however, now were at our throats—had pushed us away from prepared positions into nothingness, into howling emptiness, into a wasteland of snow. There was nothing to hold to any more. Even the soil had turned to stone, and would not admit us.

South of the village of Gonchara I met General Strecker, commander of the XI Army Corps. We had been old friends and I was very fond of him. He was a true leader, a true soldier-commander, revered by his troops to whom he was a father i and counselor. The general met me in the bunker of his chief of staff, a Colonel Grosskurth, who belonged—as I learned later-to the leading members of the secret resistance movement. Somehow, I felt that the general wanted to be alone with me.

He beckoned me to come outside. Then he began: “What are you going to do when the end has come?” - “I cannot say now what I will do, general, but most likely I shall shoot myself: I answered. His reply: “I have the same intentions, if and when circumstances permit it. But you know that General Paulus has expressly forbidden such a course.”

“Yes, I know, general, but in a situation like ours is going to be, he can no longer forbid anything.” “Do you believe that we should continue in this catastrophic way until we collapse?” “Yes, I believe so:’ I replied, “unless we make one find effort. This situation calls for unusual thinking and efforts.”

The general nodded in agreement then averted his eyes as if he wanted to scan the gray skies. Slowly he spoke: “It is very difficult to find the line of correct response and deed. An army stands and falls with the age-honored dictum of obedience. Yet this desperate situation calls for independent thinking and action.”

“This gnawing feeling of being wrong by being right, by obeying according to the book and according to tradition, is the decisive point,” I replied. “Right here in Stalingrad blind obedience becomes a farcical attitude, with nothing to do but to wait for the next pronouncement from faraway Hitler who does not believe what he “should see but sees only what he Iikee to believe. But whol will stand up and give the signal?” My bold words brought no reply. The general shook hands with me and then he slowiy turned to go to his bunker.

From army reports we ascertained that the German front had moved away from us to a distance of 130 miles. ( Figure 2.) This fact meant still less help from airplanes, particularly medical supplies, since our planes would now have to fly without tighter escort and would more and more be exposed to the increasing attacks by Russian planes. We had become an island in a seething sea.

Final Disintegration.

Shall we ever see Germany again? Maybe never. Brooding and waiting, hoping against hope with bitterness, mountting despair—such was the emotional barometer during the next few weeks. The last vestiges of rank had disappeared.

Emaciated, hollow-eyed, freezing men held on to memories now etanding out in strong relief against the misery and hopelessness about them. There was a wave of suicides by men who preferred death to a Communist prison.

Some of us expressed bitter anger at this Hitler-made deathtrap. One staffer exploded: “Now there are only 150,000 men left, but these 150,000 are all ripe fortreaeon". There were long talks about the inner motives of treason, and whether there was not treason from above against the men who slowly rotted away after having been refused permission to break through the iron ring about them. Some of the officers urged me to talk to General Paulus, knowing that I enjoyed his confidence. They felt that I should tell him about the mounting resentment toward the do-nothing attitude, this hopeless waiting for the trap to be closed. At first I hesitated, but when I finally faced General Paulus and cautiously advanced my thoughts about the morale of the troops, the sufferings and the hunger-induced lack of will to hold out any longer, he declined to listen and let me leave his bunker without another word.

The Russian tanks attacked from the north, couth, and west. Russian infantrymen looked in surprise when they found only a few German soldiers staring at them—soldiers with nothing but rifles.

Above us heavy Martinbombers went about their business without interference.

All these proud divisions that had chased the Russians over the endless eteppes now were frozen still, their guns silent, their remnante hugging the ground in long, thinned out lines that could do little more than wait for the next attack and be overrun. So it was everywhere. The Russians set their daily targets, started out in the early morning hours, and got there before the day was over—surprised at the few German soldiers who stood in their way.

Often their guns went into position in full view of our lines-with no more opposition than a solitary machinegun hammeringaway and then stopping abruptly when concentrated counterfire found iti mark.

Then the Russians started their barrage, hitting where they imagined our lines to be, often hitting a line of dead men, frozen, stiff forms, that even in death caused the enemy to be wary and waste ammunition.

Hopes, Rumors, and Plans.

Many of us discussed plans how to escape before the inevitable end would come.

Some saved provisions to enable them to keep going once they had stolen their way through the Russian lines. Others put on Russian uniform pieces to make detection more difficult. Our Russian “Matkas’’who had been working in our kitchens offered to accompany us through the steppes and to show us how to avoid Russian outposts. Escape became an obsession with many. We stopped shaving, and our exterior was anything but military.

One never knew whether his neighbor was a general or a buck private. We had become a vermin-ridden, unkempt, rankless, hungry, and desolate body of men, formerly known as the Sixth German Army.

And then rumors—always from the soldier who heard, who saw, who knew. There were phantom armies moving toward Stalingrad. There was a, landser (the German equivalent of the American G.I. ) who had learned about German tanks chasing the Russians away from Kalach. He had heard It from another landser whose friend had seen such a notice posted at the headquarters bulletin board at Gumrak. What he did not know was that there no longer was a headquarters at Gumrak and that no longer was there a village by the name of Gumrak only a heap of masonry, debris, and dust.

There still was sentiment to try one last, desperate breakthrough against the southwestern front. Some of the commanders believed that the Russian front at this sector was only thinly held and that a concentration of German troops for one final, mad rush would break the iron wall around us and permit our escape in that direction. However, this plan came to nought, mainly because of lack of combat ready troops, and also because it was thought impossible to withdraw troops from other sectors for this undertaking without the Russians learning about it in time to crush the thus depleted sectors, an additional and probably the main factor against the attempt was the low morale of the troops. They had lost their fighting spirit. The generals now were practically without an army—the army was dead tired, hungry, desperate, and had lost faith.

Mistake Is Recognized.

When I next met General Paulus he had aged visibly. His face was an ashen gray; there were deep furrows in it, marks of scourging worries and woes. His once erect carriage had yielded to a sloppy posture. His hands hung limply at his sides and his eyes showed nothing but hopelessness. He shook hands with me.

“What do you say to it all now, colonel?“ “Nothing, sir, that theother, older staff officer would not say with me.”

“And what is that?”

“Sir, You should not have obeyed. Now you have missed our chance. Late November you should have struck out with your then intact Sixth Army. And after the battle you should have gone to Hitler and offered him your head. You would have become another York.”

The general looked at me searchingly, then, in what looked like a confirming gesture, placed his hand upon my right shoulder and replied: "I know, and I also know that history already has condemned me.”

It is worth noting here that, despite rumors to the contrary, General Paulus never had left Stalingrad to appear before Hitler, and Hitler never had come to us to see for, himself.

Every tragic situation has its moments of comic relief. The “dilettante of Angerburg” (our nickname for Hitler and his headquarters in far away east Prussia) had the bad taste to, shower upon our commanding officers a rash of promotions.

We shook our heads in disbelief. Instead of armies, Hitler sent promotions to officers only a few steps away from Russian concentration camps. Paulus became a Colonel General, presumably for staying put in obedience to Hitler’s orders. His promotion to the rank of a field marshal one fortnight later was nothing but a clumsy challenge to commit suicide when the time of ruin came. For never in German Army history had a field marshal been taken prisoner. But General Paulus did not do Hitler this favor, he went into Russian captivity, with the insignia of a German field marshal on his shoulders.

At this time the chief of staff wanted to risk everything in one last concentrated attempt before the gates of Stalingrad.

East of the village of Pitomnik he wanted to prepare strong new positions to stop the Russian advance, The “front” would have to be traced in the snowy wasteland of that area, and all I could find for the purpose of throwing up fortifications were two truckload of shovels, spades, and axes. A handful of engineers served as guides in the pale winter night when the emaciated infantry started to drag themselves into these improvised lines. We had

long passed the point of the possible, had missed good chances, had let them slip by merely because the Fuhrer had other plans. Our frontlines collapsed time and again.

Von Seydlitz Bitter.

Our talks became bolder. The conspiracy grew hy leaps and bounds. We talked about far away Germany, our families, we wrote letters, not knowing how to get them out, since only a few daring pilots brought their planes down. Most of them just released their provision bombs and raced back toward their home airfields. We talked about this war that nobody wanted and how it became a war by and for the Nazi Party.

At about this time I met General von Seydlitz, commander of the LI German Army Corps, with whom I had served in the same corps during peacetime. The general invited me into his bunker. He knew from his chief of staff, Colonel Clausius, my long-time friend and comrade, that I was critical of events and that fact might have caused him to speak his mind freely and without subterfuge. He paced the bunker inceseantly, talking to me at the same time. He fairly raged against the “all highest,” his sense of values, his preferences for those with a Nazi twist rather than military knowledge.

He condemned the orders of the Sixth Army; he could not understand why a successful general like Paulus had lost his drive, his daring, his energy.

I remember so well his last words to me: “For Germany—against Hitler". I had never suspected s much vehemence as I encountered I General von Seydlitz. Yet he was right. Hitler went into Russia almost as if everything would be a foregone conclusion and he wound up crying for discarded winter clothing, even women’s overcoats, to dress his freezing German soldiers caught in the pitiless Russian winter.

Last Request Refused .

On 22 January General Paulus asked Hitler by wireless to agree to the capitulation or the breakthrough in small groups in the direction of the Calmucks steppe and there to-join the units of the First Panzer Army fighting at the Terek front. But Hitler refused the last request of the commander of a dying army.

We talked about our wives, parents, children, towns, and friends. At times we joked about a Stalingrad shield that Hitler surely would design with his own artistic hands. It no longer mattered—Russian tanks already were prowling not far from us. Captain Fricke talked to me about his young wife, about their recent honeymoon, and how he would walk all over Siberia and back just to see her again. He did not see her again. There was a major without a battalion, because his battalion had just disappeared, ground into blood and dust a little while ago. His mind had been affected by this tragedy, and he sat in a corner and stared emptily ahead.

Sudden Orders to Leave.

At about this time my telephone rang. My friend Adam was speaking. “You are flying out tomorrow as a courier",

“Yes, and back when?”

“Man, do you not know what that means? You do not come back.”

I was numb for a moment, then a strange reaction took place. Yes, and what would the others say, when I leave now?

Comradeship is not just a word to an honorable man. If it has welded together men in uniform in a tragic fate like ours, it has strong, very personal implications, I looked over to the major whose battalion was lost.. He looked at me in a beseeching way, his eyes flickering.

Adam spoke again. “You are to report to the commanding general and his chief of staff tomorrow morning at ten o’clock.” And then the reaction set in, a tumultous surge toward a new life, thanking God for this last chance out of my own grave, out into the sunlight, into life.

Next morning, as I, was getting ready, my orderly Blueher came into my bunker.

“Sir,I have a wife and two small children at home.” Then he burst into convulsive sobs. “I know, Blueher, but I cannot promise you anything—yet. At any rate, prepare your knapsack. You come along the airfield.” Blueher’s eyes lit up. There was hope.

I faced Major General Schmidt, the chief of staff, ‘for the last time. I was shocked at his change of appearance. This knightly gentleman had kot shaved for days. His deep-set eyes looked emptily at me. His uniform was in need of cleaning His hands were folded in front of him, resting on his desk, as if praying inwardly. We talked at length, and finally he rose with these, his last words to me: “Tell wherever’ you deem it wise and possible that the Sixth German Army was betrayed by the all highest, and left in the lurch.” Had he taken this view a few months earlier so much tragedy might have been averted.

Gumrak airfield already was under Russian artillery fire. On my way there I passed long rows of Romanian troops, a pitiful picture, remnants of the burned out 1st Cavalry and 20th Infantry Divisions.

Dead, dying, wounded, and those still untouched lined the road, a most macabre frame for my last impressions before reaching the field. Colonel Rosenfeld, formerly a well-known police boxer, received me and asked me into a makeshift bunker to wait for darkness when planes could be expeeted to land.

The bunker was filled with soldiers. A young army chaplain entered, asking Whether anyone knew where his division could be located. Nobody knew. A wounded soldier stepped up to the young minister. "Do you believe, Herr Pfarrer, that God wants us to die here?” “Yes, if it is His will.He has the last word in every human deed,but this word does not always have to be a Yes. And if He, in this dire hour, denies Himself to us, so is this a sign that our own works and deeds have not His approval:" Thus spoke the chaplain, and

I envied him for his simple, deep belief.

Last Flight to Safety.

At dusk we left the bunker to be near the landing apron. Nat far from us we saw the flashes of Russian guns. Around us small fountains of dirt shot upward where a shell had struck. Now we heard motors—near at first, then farther away. Here it comes, a Ju 52, in a steep descent to make the improvised, short runway. It stopped in front of us, idling its motors

because of the terrific cold. Quickly a number of men emptied the plane of its foodstuffs, medicine, three barrels of oil and 15 six-inch shells. Fifteen, when 15.000 are needed for one counterthrust!

Then they came-the wounded, the dying, the sick; and there was room for only 20 men. I had given my orderly Blueher quiet instructions to stay in the storage section of the plane. I could see the gratefulness welling up in his eyes.

The soldiers milled around the plane. The military police were helpless. I carefully picked the most seriously wounded, checked their medical papers, and let them enter -only a pitiful 18.

The motors started and slowly the Ju 52 rose. Soon we were over the Russian positions, and we saw the flashes of Russian shells. I folded my hands and I saw Blueher and the others do the same. We said thanks to God above us-and we prayed for those left behind in hell.