ON 30 JUNE 1942 the Sixth Army had left its

jumping off point east of Belgorod, and was

advancing for the attack. After two days of hard

defensive fighting the Russian resistance

appeared to be broken, and the Germah units went

over to the pursuit. It appeared, however, that

the Russian retreat was being conducted on the

basis of previous plans, for during the delaying

action of the withdrawal to the southeast not a

single article of equipment was left behind and

the number of prisoners taken was small. The

extensive Russian minefield considerably slowed

the German advance. But by 20 July 1942 the main

body of the Sixth Army was astride the upper

course of the Chir.

The Sixth Army South of the Don.

The original German plan of operations had

called, for the conquest of the southern Russian

area in chronological phases. First, Army Group

B, with its Sixth Army and First and fourth

Armored Armies, was to seize Stalingrad and the

lower Volga and establish a defense front

between the Don and the Volga. After this, Army

Group A was to seize the Caucasus area to the

south. The German Supreme Command (Hitler)

looked forward to the enemy’s collapse as a

result.

It was fairly

certain that the strategic objectives of this

plan would be reached before winter, even though

the resultan anticipated had to remain very

doubtful, if not dismissed as purely Utopian.

However, in view of

the successful advance of the Sixth Army, the

High Command decided that the Soviet defense was

so shattered already that only fractional forces

were now necessary to bring about the collapse

of the Don-Volga front. Under the impulse of

this wishful thinking, the original operations

plan was discarded and a new directive issued

which allotted to Army Group B with its Sixth

Army and Fourth Armored Army, the Don bend -

Volga bend operations objective while, at the

same time, Army Group A was assigned the mission

of the conquest of the Caucasus area. The idea

of any point of main effort was dissipated by

this dispersal of forces.

The Battle of Kalach.

On the basis of the

manner in which operations had proceeded up to

that point

and with the forces available, it seemed logical,

in July 1942, that the Sixth Army would reach

the crown of the great Don bend at Kalach in a

few days. But many rapid moving, hard-hitting

units, and large quantity of transport materiel

were transferred to Army Group A with the change

in plans. At the moment (22- 24 JuIy) when

everything depended on rapid action and

concentrated effort, an armored division and two

motorized divisions were left without transport

and incapable of movement.

About the same time,

the Russian Command obviously had decided to

defend Stalingrad, not at the gates of the city

but on the west bank of the Don, and on 25 July

assembled forces in the hilly country northwest

of Kalach. A battle took place which put the

Sixth Army formations (which were in a critical

situation with respect to supply) in a most

difficult situation.The enemy not only brought

forward his armored and infantry divisions at

Kalach, but also those farther north in the

vicinity of Akimovskiy across the Don. As a

result of this, the Sixth Army was obliged to

fight a battle on two fronts.

It was forced from

successful pursuit to defense.

The massed Russian attacks, supported by

hundreds of tanks, eventually were repulsed.

After 10 days of the

hardest defense fighting, supplies began

arriving again on

the German side. The divisions again began to

receive motor fuel and ammunition from the

supply bases hundreds of miles to the rear. The

German Army gained the initiative. It saw the

opportunity not only of beating the enemy

installed in a broad, risky semicircle about

Kalach, but of annihilating him by a double

pincers action along the Don.

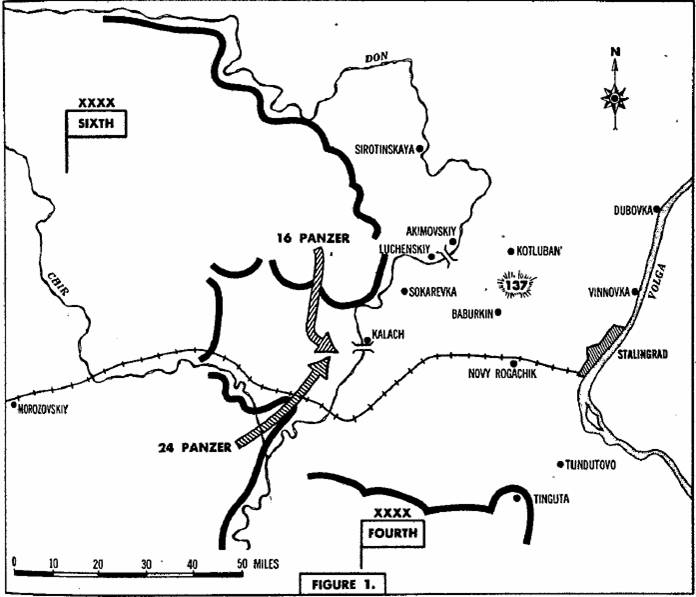

The attack began early in the morning of 7

August; about 20 hours later, the points of the

16th Armored Division (from the north) and of

the 24th Armored Division (from the south ) met

on the heights west of Kalach.

The Russian Sixty-fourth Army and the First

Armored Army, cut off by this operation;

capitulated three days later.

The enemy - in addition to many casualties -

lost 1,000 tanks and 750 guns. Fifty two

thousand Russians were taken prisoner. However,

the combat strength of the Sixth Army divisions

also had been seriously impaired. Their losses

were felt more since replacements were not

available.

On 29 July General

von Paulus had declared that: “The army is too

weak for the attack on Stalingrad”. And a day

later, the Chief of the Army General Staff,

Major General Schmidt said: “The farther east we

get the weaker we become.” His urgent request

for two or three infantry divisions was turned

down. The combat strength of the Sixth Army was

reduced still further on 10 August by the

withdrawal of an armored and an infantry

division.

The enemy had been beaten in a battle of

annihilation. He had, however, gained time—which

he employed in a most advantageous way—by his

decision to prepare a defense position west of

the Don. In view of his inexhaustible human

reserves this gain of time was of greater weight

than the losses he had suffered at Kalach.

Attack Across the Don.

At dawn on 21 August two divisions crossed the

Don in the face of violent enemy defense action.

By evening they had secured a wide bridgehead.

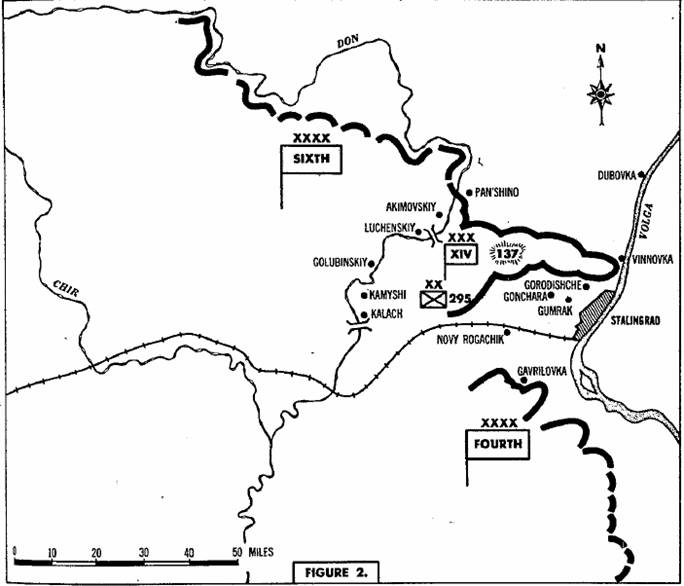

At noon, 22 August, the 16th Armored Division

and the 3d Motorized Division of the XIV Armored

Corps crossed the Don and made ready, in the

bridgehead, for their attack eastward.

On the same day

General Panlus declared: “ We shall attack

tomorrow from the bridgehead with all our forces,

over Hill 137. If it succeeds, we must count on

the mobile divisions alone remaining for a while

on the hills northwest of Stalingrad. The 76th

and 295th Divisions have little combat strength,

so that the thrust will not be strong—particularly,

we shall have difficulty in the matter of cover

on the south I repeat it once more, that we are

two infantry divisions short".

This estimate of the

commander in chief of the army was to find its

full confirmation in the way the fighting

progressed during tbe following weeks. The 16th

Armored Division had 81 tanks at its disposal,

and the 3d Motorized Division had 42. A few days

later the 60th Motorized Division arrived with

40 additional tanks. Altogether, therefore, the

Sixth Army had only 163 tanks for its attack on

Stalingrad.

The Drive to the Volga.

On 23 August the XIV

Armored Corps drove forward over Hill 137 and to

the east, securing itself with weak fractional

forces in the Kotluban area against enemy action

from the north. By 1700 the scout tanks of the

16th Armored Division were already south of

Vinnovka on the steep bank of the Volga.

The terrain gain was deceptive, for a very large

number of enemy groups still remained behind in

the area passed through. The LI Army Corps,

setting out from its bridgehead position,

reached a line north of Baburkin with its 295th

Division. (Figure 2.)

Since interruption

of the weakly held terrain bridge between the

Don and the Volga could be expected during the

ensuing night, air supply of the XIV Armored

Corps was ordered.

On 24 August the

Russians counterattacked with numerous tanks

from the direction of Dubovka and Panshino. The

Akimovskiy bridge across the Don was partially

destroyed by Russian bomber attacks with the

result that this military route was closed to

traffic for two days.

The expected interruption of the highway east of

Hill 137 was brought about on 25 August. The

connections of the XIV .Armofed Corps with the

west were now broken. A combat team from the

60th Motorized Division, which was crossing

theDon, was given the mission of opening the way

to the east again. The 71st Division forced its

way across the Don north of Kalach and took

Kamyshevski. At the same time the 295th Division

was progressing to the south.

The following figures show how matters stood

with regard to the combat strength of a number

of divisions:

The376th Division, 28 percent; 398th Division,32

percent; 384th Division, 30 percent; and the

305th and the 71st Divisions, 36 percent. They

were reduced, therefore, to companies of from 40

to 50 men.

In contrast with this the companies of the

Russian infantry division showed strength of

from 150 to 180 men.

The Outcome.

The XIV Armored Corps was placed in such a

threatening situation by a powerful, methodical

Russian attack—from both the north and south—that

the corps command proposed its Volga group move

to a position back of Hill 137 during the night

of 26-27 August. Since the highway was now cut

on Hill 137 itself, the Army High Command turned

down this proposal very emphatically and

demanded resistance a outrance until the LI Army,

Corps, attacking from the west, should bring

relief. This corps finally arrived on 29 August.

The drive against Stalingrad itself had to be

halted. It was resumed again hy an army group

order on 30 August, since the Fourth Armored

Army on that day had ruptured the Russian lines

at Gavrilovka.

Best Regards.

For this reason the Sixth Army, in spite of the

extremely critical defense situation, directed

the XIV Armored Corps and the LI Army Corps to

attack in a generally southern direction with

the final objective of annihilating the enemy

forces west of Stalingrad.

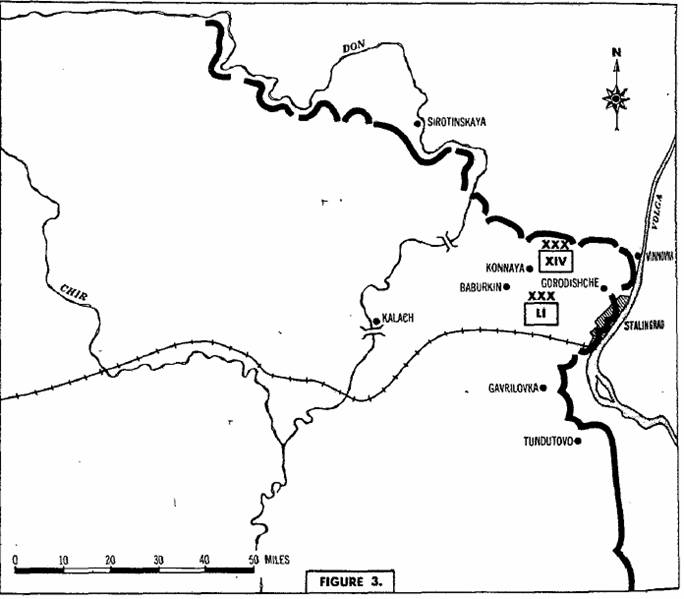

While a strong

Russian attack from the north—against the

positions of the XIV

Armored Corps—was

repulsed on 2 September, the fractional forces

of the 60th Motorized Division and 295th

Division gained ground in the direction of

Gonshara-Gumrak.

Early on 3

September, contact was established southeast of

Gonshara with the 24th Armored Division of the

Fourth Armored Army. Even thoug a considerable

tactical success had been achieved, on the same

day the northern front of the XIV Armored Corps

again was badly overrun by the Russians. It was

only possible to repel the Russian attacks at

the cost of serious losses, and the use of the

artillery of the 60th Motorised Division which

was fighting with its front to the south.

An enemy attack of from nine to ten infantry

divisions and five to seven armored Brigades

against the north occurred on 5 September.

By the use of all

available reserves and the expenditure of

unusual quantities of ammunition—and at the cost,

again, of very considerable losses—they were

repelled.

The loss of 114 tanks on the Russian side did

not, in view of the increasingly critical

situation of the XIV Armored Corps,give rise to

any illusions. The combat strength of the German

armored infantry and rifle regiments visibly was

disappearing; ammunition reserves were dwindling

as a result of insufficient transport capacity.

The mobile units of the armored corps were being

worn down. Two days later the LI Army Corps

succeeded in effecting a four-mile-deep

penetration on both sides of Gorodishcbe, which

on 9 September was widened in a northerIy

direction against a bitterly fighting enemy.

Toward the City.

On 13 September the

LI Army Corps set out to the southeast toward

the heart of the city of Stalingrad, whose

outlying areas were taken. On the following day,

two divisions with about a one-mile front,

forced their way through the city and all the

way to the Volga. The main railway station fell

into their hands. For the continuation of the

attack on Stalingrad, on 15 September, three

divisions of the Fourth Armored Army were placed

under the orders of the Sixth Army.

The attack of the two corps gradually cut its

way into the city in costly house to house

fighting. (Figure 3.) In three days the LI Army

Corps lost 61 officers and 1,492 men.

As the resuIt of our own attacks and the repulse

of the Russian counterattacks, the infantry

forces between the Don and the Volga had become

so weakened that theGerman Army High Commend

again requested additional units. Divisional

combat strengths of from 500 to 800 men,

including the officers and noncommissioned

officers, were the rule. Finally it was agreed

that three infantry divisions wouId be with rawn

from the southern front for

the use of the Sixth Army.

In addition to the need for more forces there

was a growing shortage of ammunition for

10-centimeter and 7.5-centimeter cannon, and

8-centimeter mortars. The heavy mortar regiment

was without a round of ammunition.

The reverse of this was true in the case of the

enemy, who had continuing reinforcement and

supply.

On 23 September the

Soviet tanks drove through the main line of

defense in the east wing of the VIII Army Corps

south of Kotluban, and cut the supply route

north of Bal Rososhka, where they were destroyed

on 25 September.

The impossibility of making up for the heavy

losses of the frontline units, reduced to

one-third or one-fifth of their original

etrength, the insufficient supply, and the

continually increasing enemy resistance were

matters which required halting the attack on the

Stalingrad blood mill, and indicated the

necessity for pulling back the front at least to

the west bank of the Don. The objection that

such a withdrawal movement was prohibitory

because of Army Group A, which was fighting in

the Caucasus, was without foundation, for its attack, too,

was halted due to lack of forces.

Every attempt at

resuming the attack thus far had failed in the

face of the stubborn resistance of the

numerically and equipment-wise superior enemy.

The hopelessness of the prospect of being able

to achieve the objectives assigned to Army Group

A should have led to a withdrawal to the lower

course of the Don or to the east side of the

Crimean peninsula.

But the requests and

proposals of Army Group B and of the Sixth Army

fell on deaf ears. Serious opposition to

Hitler’s measures, as leader, had, up to this

point, led only to the deposition of the

objectors.

And so, for the Sixth Army the trail was blazed

to catastrophe.